"You’re going to America just for a marathon?"

The lady at the immigration desk in Mumbai seemed amused by my answer.

With marathons happening in India nearly every weekend,

traveling 10,000 miles to run just 26 miles might not make sense to most

people. But when you've experienced one of the World Marathon Majors, you're

bound to want to run the others.

I didn’t know how many runners on my flight were headed to

Chicago for the marathon that weekend. But on the return flight, more than a

quarter of the passengers were wearing either a Chicago Marathon medal or

jacket. People from different parts of the world, regardless of age, race, skin

color, or the language they speak, were connecting easily. Running is the

common thread. The language of running breaks the ice, no matter how thick. You

meet new friends, reconnect with old ones.

“Are you on Strava?” — and a friendship begins.

When should you arrive for an international marathon?

Some might say to come a day earlier and do some sightseeing after the race. I

chose to arrive four days ahead of time to shake off the jet lag, soak in the

city’s energy, and get in a couple of shakeout runs while exploring.

The marathon expo is similar everywhere: chaotic, with

runners searching for shoes, gels, and other essentials, queuing for race

souvenirs, and catching up with friends. The international flavor is

unmistakable, as runners from around the world check out new products and try

on the official race gear. It’s the same at every major marathon.

The day before race day is the hardest.

Should I sleep? Should I take a walk? Maybe visit a friend? There’s the Nike

Finisher Jacket just launched , go grab it —it might sell out after the race.

There’s a new shoe on the market, On Cloud, that might not be available back

home. What should I eat? What food here has enough carbs? Am I drinking enough

water? What should I wear on race day? What time should I set my alarm,

assuming I even sleep?

Even for an experienced runner, these questions cause

stress.

Since arriving in the U.S., I hadn’t been sleeping well—just

a few hours each night. But on the night before the marathon, surprisingly, I

slept for five solid hours. This never happens before a race because of

anxiety. It felt like a good omen.

My race was scheduled to start at 8:00 AM, so I arrived at

6:30 AM. It was cloudy and cold, and the corral was nearly empty. I realized I

was too early. That was my first mistake. I had to spend two hours waiting in

the open. I found a corner and sat on the curb near some Americans. Slowly, the

corral began to fill up. To pass the time, I struck up conversations. Americans

are very friendly, and marathon talk was on everyone’s mind. A woman nearby was

running her first marathon, another man was doing his 17th Chicago Marathon,

and another runner was chasing the Marathon Majors like I was.

In my opinion, standing at the starting line requires

more effort than finishing the race. You

think about all the training plans, the missed runs you had to make up for, the

strength training, the travel across 10,000 miles, and the stress of navigating

an unknown country.

Due to the large number of participants, the organizers

split the race into three waves, with the first starting at 7:30 AM and the

others 30 minutes apart. After the national anthem, we heard the flag-off for

Wave 1. I was in the second wave and eagerly awaited our start, only to realize

they were flagging off each corral separately. Apparently, there were about

15-20 different flag-offs!

Our corral (J) didn’t actually start until 8:30 AM. So I ended up spending

nearly two hours in the cold. If you ever run the Chicago Marathon, arriving

just 30 minutes early would save you a lot of trouble, especially when it comes

to porta-potty visits.

Though waiting in the corral was uncomfortable, this format

had its advantages—the race never felt overcrowded. Unlike Berlin and London, I

always had the blue line beneath my feet, without having to zigzag around

slower runners.

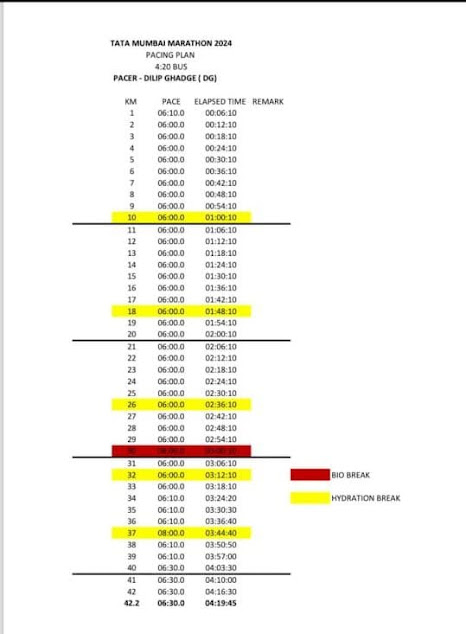

The pacer dilemma.

Because of Chicago’s well-known GPS issues, watches often show incorrect

distance and pace, especially in the first 5 kilometers. To avoid this

confusion, I decided to follow a pacer. In my last race, I missed my 4-hour

target by 90 seconds, so I aimed for a 3:55 finish here, hoping that if I

missed the moon, I’d still land among the stars.

I spotted the 3:55 pacer in the corral, but as the race

started, I lost sight of him. Chicago pacers don’t carry the tall,

distinguished flags like in other marathons. Instead, they hold small placards

with blue lettering on a white background. You really have to look hard to spot

them. I finally found a pacer at the 5K mark, after the GPS issues subsided,

and settled into my planned pace.

Though I tried running with the pacer group, I quickly

realized it wasn’t for me. Sometimes they felt too slow, other times too fast.

I always felt like I was being left behind, which stressed me out and made me

lose confidence. Many pacers believe in running negative splits, where they

take it easy in the first half and push harder in the second. But I know my

weakness—I slow down at 35K, so I don’t have the luxury of taking it easy in

the first half.

At the 10K mark, I decided to leave the group and run ahead.

After a few miles, I found another 3:55 pacer. Chicago Marathon’s pacing groups

aren’t as large as Berlin’s, which makes it easier to overtake them. I ran with

this group for a few minutes before moving ahead.

I was manually resetting my laps as the distance on my watch didn’t match the

course. If I wanted to finish in 4 hours, I couldn’t rely on my watch, but had

to follow the course markers.

Motivation and mental tricks.

You always need motivation to keep running, especially over

a distance like 42 km. After the initial euphoria, your energy dips and so does

your pace. With both pacers behind me, I started focusing on random runners

ahead, particularly those in bright T-shirts. I’d tell myself, "I’ll

follow this lady until the next signal," and after passing her, I’d pick

another runner to chase. This pattern continued until the 30 km mark.

The crowd’s support was incredible, with every part of the

city embracing the marathon like a festival. Creative signs with funny slogans

made runners smile and forget their pain, at least temporarily. But when you’re

chasing a time goal, you tune out the crowd and focus on your watch, making

their cheers just background noise.

When someone asks if the scenery was beautiful along the

route, my answer is, “I wouldn’t know. I spent the whole race staring at my

watch and following the blue line on the road.”

The Route

Chicago’s course is straightforward—the only curve you find

is a learning curve. The streets are laid out in a grid, with every block and

intersection of the same length. Even without checking his watch, a local could

calculate distances by counting intersections. While this grid system dates

back to the 1830s, it wasn’t the first of its kind—Mohenjo Daro in the Indian

subcontinent had a similar layout as far back as 2600 BC, though we can’t run a

marathon there.

The first five kilometers of the race take you past iconic

skyscrapers, which I had visited in the days before the race. Some spectators

were even lucky enough to watch from the ledge of Willis Tower. But running

through the city is always the best way to experience it.

After downtown, the route moves into the residential

neighbourhoods of the North Suburbs. The streets here are wider than those in

London or Berlin, making it easier to follow the blue line. As we loop back

into downtown, if you’re relaxed enough to look around, you’ll see flags and

supporters from various cultural groups. I even grabbed a water bottle from a

Mexican support group.

You cross the Chicago River several times during the race.

The bridges are made of steel plates with gratings, which can feel odd running

on it . Some sections are carpeted to prevent slipping in case of rain. These

movable bridges allow boats to pass, and if you’re lucky, you might spot one

raised in the distance. The Chicago River is unique; its flow has been reversed

to prevent city drainage entering Lake

Michigan, which keeps the city cool with its breeze.

Despite the history, architecture, and beauty around me, I

sometimes felt alone in the crowd. It was as if the other runners were merely

side characters in my story.

By 30 km, my brain was too focused on keeping my body moving

to spot new pacers. I saw a runner in a bright orange shirt and decided to

stick with him for a few blocks, but my mind wandered, and I lost him. This

happened several times, and the pacing trick wasn’t working anymore.

Nutrition was also a challenge. I tried a new strategy with

Maurten hydrogel plan , which I hadn’t tested in training, and it backfired. By

mile 18, I was bloated and my stomach hurt. I couldn’t focus, which was my

second mistake. I didn’t dare to consume any more gels .

I also gambled by running without my usual hydration belt. Relying on the

course's aid stations was fine in theory, but in practice, I missed having my

own water. The stations provided cups, not bottles, and I couldn’t drink enough

without slowing down. By the last 10K, I was feeling severely dehydrated. That was my third mistake.

Despite these issues, my pace remained steady, and I kept

pushing, glancing at my watch and calculating the time remaining. As the race

turned back downtown, I knew I was on the edge of my goal. I pushed harder,

even though my mouth was dry, and my body screamed for water.

With 1 mile to go, I had 10 minutes. With 1 kilometer to go,

I had 7 minutes left for a sub-4 finish. I didn’t feel the famous incline on

Roosevelt. At 400 meters to go, my watch showed 3:57. Like in London, I was

tempted to let it go, but then I reminded myself—"No, Dilip, you may

never get this chance again. You’re not dying, so keep going."

At that moment, the runners around me were pushing for the

finish line. I tried to smile and run, even though both were difficult. I

crossed the finish line at 3:58, feeling neither joy nor achievement—just sheer

relief.

I didn’t feel like calling anyone; I knew my friends and

family had been tracking me. I collapsed on the sidewalk and lay down. After a

few minutes, a volunteer helped me up, encouraging me to walk. I felt intense

cramps in my calves but managed to reach the medal station. I received my medal

mechanically, not caring for a photo. I gulped down some water, but I still

felt nauseous.

“I’ll never run a marathon again.”

That thought crossed my mind as I collapsed on the curb once more, crying out

in pain from the cramps.

I wandered into the party zone, feeling much better after

resting. The Chicago skyline looked stunning beneath the dark clouds, and the

sound of happy chatter in countless languages filled the air. My cramps were

gone, and I realized—there was no reason not to be happy.

I grabbed a beer can from the counter and smiled. Yes, I had finally achieved my sub-4 dream.

.jpeg)